Published

More books for the never ending list

More books for the never ending list.

- What Tech Calls Thinking, Adrian Daub, 2020 (read introduction)

- The Broken Branch: How Congress Is Failing America and How to Get It Back on Track, Thomas E. Mann & Norman J. Ornstein, 2006 (read excerpt)

- The City We Became, N.K. Jemisin, 2020 (read excerpt)

And a few excerpts / quotes from current reading that I’m finding extremely useful and relevant.

If the gloomy vision of a dehumanized world which has just been evoked is not to become a reality, some complete readjustment must be made, and at least two generations have found themselves unequal to the task. The generation of Thomas Henry Huxley, so busy with destruction as never adequately to realize how much it was destroying, fought with such zeal against frightened conservatives that it never took time to do more than assert with some vehemence that all would be well, and the generation that followed either danced amid the ruins or sought by various compromises to save the remains of a few tottering structures. But neither patches nor evasions will serve. It is not a changed world but a new one in which man must henceforth live if he lives at all, for all his premises have been destroyed and he must proceed to new conclusions. The values which he thought established have been swept away along with the rules by which he thought they might be attained.

To this fact many are not yet awake, but our novels, our poems, and our pictures are enough to reveal that a generation aware of its predicament is at hand. It has awakened to the fact that both the ends which its fathers proposed to themselves and the emotions from which they drew their strength seem irrelevant and remote. With a smile, sad or mocking, according to individual temperament, it regards those works of the past in which were summed up the values of life. The romantic ideal of a world well lost for love and the classic ideal of austere dignity seem equally ridiculous, equally meaningless when referred, not to the temper of the past, but to the temper of the present. The passions which swept through the once major poets no longer awaken any profound response, and only in the bleak, tortuous complexities of a T. S. Eliot does it find its moods given adequate expression. Here disgust speaks with a robust voice and denunciation is confident, but ecstasy, flickering and uncertain, leaps fitfully up only to sink back among the cinders. And if the poet, with his gift of keen perceptions and his power of organization, can achieve only the most momentary and unstable adjustments, what hope an there be for those whose spirit is a less powerful instrument?

And yet it is with such as he, baffled, but content with nothing which plays only upon the surface, that the hope for a still humanized future must rest. No one can tell how many of the old values must go or how new the new will be. Thus, while under the influence of the old mythology the sexual instinct was transformed into romantic love and tribal solidarity into the religion of patriotism, there is nothing in the modern consciousness capable of effecting these transmutations. Neither the one nor the other is capable of being, as it once was, the raison d’être of a life or the motif of a poem which is not, strictly speaking, derivative and anachronistic. Each is fading, each becoming as much a shadow as devotion to the cult of purification through self-torture. Either the instincts upon which they are founded will achieve new transformations or they will remain merely instincts, regarded as having no particular emotional significance in a spiritual world which, if it exists at all, will be as different from the spiritual world of, let us say, Robert Browning as that world is different from the world of Cato the Censor.

As for this present unhappy time, haunted by ghosts from a dead world and not yet at home in its own, its predicament is not, to return to the comparison with which we began, unlike the predicament of the adolescent who has not yet learned to orient himself without reference to the mythology amid which his childhood was passed. He still seeks in the world of his experience for the values which he had found there, and he is aware only of a vast disharmony. But boys—most of them, at least—grow up, and the world of adult consciousness has always held a relation to myth intimate enough to make readjustment possible. The finest spirits have bridged the gulf, have carried over with them something of a child’s faith, and only the coarsest have grown into something which was no more than finished animality. Today the gulf is broader, the adjustment more difficult, than ever it was before, and even the possibility of an actual human maturity is problematic. There impends for the human spirit either extinction or a readjustment more stupendous than any made before.

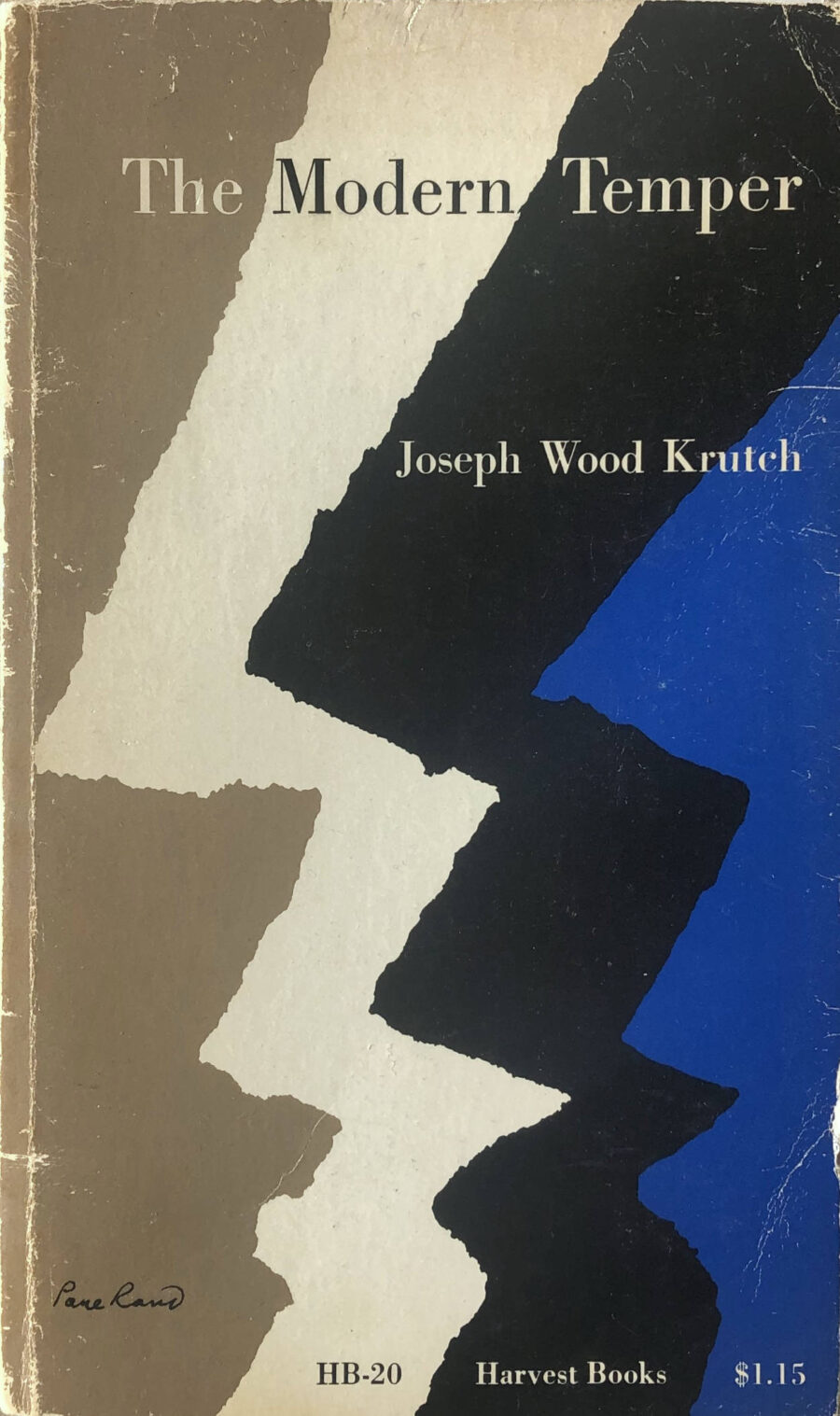

The final pages of the first chapter, “The Genesis of a Mood”, from The Modern Temper by Joseph Wood Krutch, first published in 1929

I picked up a copy of this and a few other great secondhand books from the Alley Cat Bookshop in the Mission.

I understand that The Modern Temper has a pretty pessimistic outlook overall which might make it tough to finish, particularly in the current circumstances… But I’d like to finish it. Even though it was published almost a century ago, the feelings and psychological maladies that Krutch describes are more relevant than ever. The painful, unending cynicism. That unchecked growth and progress have incalculable ramifications on human consciousness, that we must be more wary of the consequences.

I’d like to follow it up with his book The Measure of Man from 1954 where he supposedly considers the modern world more optimistically, and possibly with the nature books he wrote later in life while living in Arizona.

What follows is a Duchampian door, at once open and closed, logical and whimsical, focused and drifty, academic and anecdotal. Part explanation, part justification, part reification, and part provocation, it’s a memoir of sorts, an attempt to answer a question I often ask myself regarding UbuWeb: “What have I done here?” Is it a serendipitous collection of artists and works I personally happen to be interested in, or its it a resource for the avant-garde, making available obscure works to anyone in the world with access to the web? Is it an outlaw activity, or has it over time evolved into a textbook example of how fair use can ideally work? Will the weightlessness and freedom of never touching money or asking permission continue indefinitely, or at some point will the proverbial other shoe drop, when finances become a concern? The answer to these questions is both “yes” and “no”. It’s the sense of not knowing—the imbalance—that keeps this project alive for me. Once a project veers too strongly toward either one thing or the other, a deadness and predictability sets in, and it ceases to be dynamic.

From the introduction to Duchamp Is My Lawyer: The Polemics, Pragmatics, and Poetics of UbuWeb by Kenneth Goldsmith, published this year

But there is so much more that I’ve underlined and noted in this book. Very worth reading, particularly for anyone dealing with creative copyright and / or the web these days. Get it from Columbia University Press.