Published

Selecting open, free, or commons licenses for content and code

Content and code licensing is a bit of a minefield.

The first thing to remember is that in the UK and USA at least, all creative works are automatically protected by copyright from the moment they are made. The creator retains exclusive rights to their work, and nobody can share, copy, or use the work without the creator’s direct permission unless they are sharing it in fair use (critique, comment, parody, etc.). This is the reasoning behind the classic “all rights reserved” statement you often see in relation to a creative work.

But it is foolish to believe that “all rights reserved” will always be respected for content online. Tumblr and other platforms have made it so effortless to share others’ work that the public perception of copyright is seriously warped. Creators are very welcome to reserve their rights to all of their work but if they’re releasing it online under such terms, they should be prepared for a lot of violations.

The nature of the Internet created a need for less restrictive copyright licenses, and a whole host of open, free, and commons licenses have filled the void. This is my experience navigating the space for my own work including some of the resources I’ve used, the licenses I have chosen, and my reasoning.

Content licensing

It is realistic to expect the content you share online to be shared by others regardless of whether or not it is licensed. Some will intentionally misuse it, but most will be unaware and do so accidentally. To remove doubt and to avoid fighting against this reality, it can be worthwhile to release your content under a clear license that permits sharing under certain terms.

The Creative Commons licenses offer such terms and are possibly the most widely-used content licenses on the web. They encourage openness, are clearly worded, are easy to select using their license chooser, and they’re professionally written. There are a few caveats though.

Once you have released something under a Creative Commons license, you can’t revoke that permission. If someone uses one of your images in a way you don’t like, for example to promote a cause you can’t stand, there is nothing you can do about it if they have shared it within the terms of your license. You can revoke the license from that image moving forward, but it won’t affect past usage.

It is also on you to police the usage of your work. If you share your work online then this is a chore regardless of licensing, but it might be a bigger task for work released under a Creative Commons license since it encourages sharing. Google’s reverse image search can be useful for policing the use of your images online. There are also a lot of plagiarism detection services that can detect when your content is being copied, but a lot of these come with a premium price tag.

Finally, if you are keen on releasing your content in a way that conforms to Free Software Foundation (FSF) principles, note that most Creative Commons licenses are considered non-free.

Since I’m comfortable with these stipulations, the content that I create and publicly share on my website is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License unless otherwise stated. This license permits the sharing and adaptation of my content under the following terms:

Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

ShareAlike — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original.

There are certain cases where I would not be willing to release my work under a Creative Commons license. I might hesitate if the work has shared authorship; if a lot of people have been involved in creating a piece of work, it could be a struggle to get permission from all of them to release the work under this license. There are also certain images that I might decide not to release under a CC license, images that are particularly sensitive or precious to me in some way.

If I were not willing to release something under a Creative Commons license though, I would probably avoid sharing it publicly online at all. Otherwise, I might consider konomarking the work to invite others to get in touch regarding permissions.

Software licensing

If you openly share software code that you have written intending for others to use it, you need to give it a license. If your software has no license, users can only assume that you reserve all rights and don’t permit the use of your software.

There are a range of open source software licenses to choose from. The FSF has a good licensing resource page, and the Open Source Initiative (OSI) has a categorised list of open source licenses. The website choosealicense.com offers a simple license picker (note that though it’s an excellent tool, it’s not a comprehensive guide).

To select a license for the WordPress theme I wrote for this website, I reviewed these resources and then consulted the dependencies.

WordPress is released under the GNU GPLv2 (or later) license. As they state on their license page:

Part of this license outlines requirements for derivative works, such as plugins or themes. Derivatives of WordPress code inherit the GPL license. […] There is some legal grey area regarding what is considered a derivative work, but we feel strongly that plugins and themes are derivative work and thus inherit the GPL license. If you disagree, you might want to consider a non-GPL platform […] instead.

On top of that, a theme and all of its contents *must* be under a GPL or GPL-compatible license to be allowed in the WordPress theme store. It makes sense for me to abide by this rule since I may eventually circulate the theme in the store, though I don’t currently. There are a lot of GPL-compatible free software licenses, but we’ll put that aside for the moment to address the next dependency.

Infinite Scroll is released under dual licenses, commercial and open source. To qualify for the open source license, I have to release my code under a license that is compatible with the GNU GPLv3 license. There may be fewer licenses that are compatible with GNU GPLv3 specifically according to the wiki.

My other dependencies such as Prism.js by Leah Verou and a whole bunch of Gulp packages are released under the MIT, Apache, or ISC licenses. These are all compatible with GPL according to the FSF.

Based on all of this, it makes the most sense for me to offer my theme under the GNU GPLv3 license. It is most compatible with the licenses of my dependencies, and it offers terms that I am happy with. It’s a long license so it can be a little complicated to decipher, see this summary from tl;drLegal or GNU’s quick guide for more information.

Copyright notice wording

After selecting a license for my content and code, I needed to add the information somewhere prominent.

Since my site doesn’t have a footer, I added a notice in the menu on every page stating that many rights are shared and that further information can be found in the details and guidelines.

In my theme’s GitHub repository, I added the license in their preferred manner to create a license.md and display a license icon in the repo status bar above the list of files.

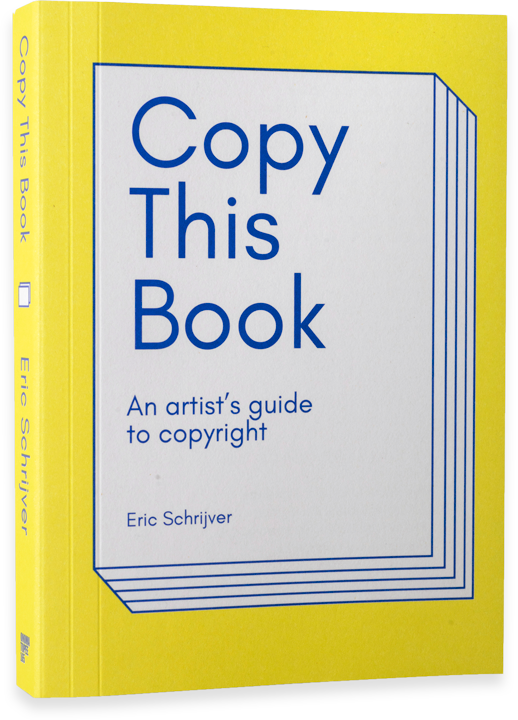

Copy This Book: An Artist’s Guide to Copyright by Eric Schrijver (Onomatopee, 2018) is my very favourite resource on copyright. It is such a practical, thorough, and gently-worded guide to a very thorny topic. The image above is from the Copy This Book website under a CC-BY NC 4.0 license.

This is a summary of the research I have done on the topic and should be taken with a grain of salt. For expert guidance, consult an expert! If anyone out there has additional guidance on the topic to share, let me know. More thoughts coming soon on ethical open source licensing…